Ⅰ.

I think it is the circle, as a formal element that runs through the work of Cho Kheejoo. Cho is an artist who has continued to experiment with various media and formats such as video and animation as well as painting and three-dimensional. With more than 30 solo exhibitions, she has been active not only in various experiments with art media, but also exploring the humanities, natural sciences, and various art discourses. From1979, she started to use circles in her paintings. At that time, she painted and drew different sizes of circles and sometimes they became dots. Since 1981, circles become one of the most important elements, visualizing not only the dynamics on her paintings, but also her various interests in other fields.

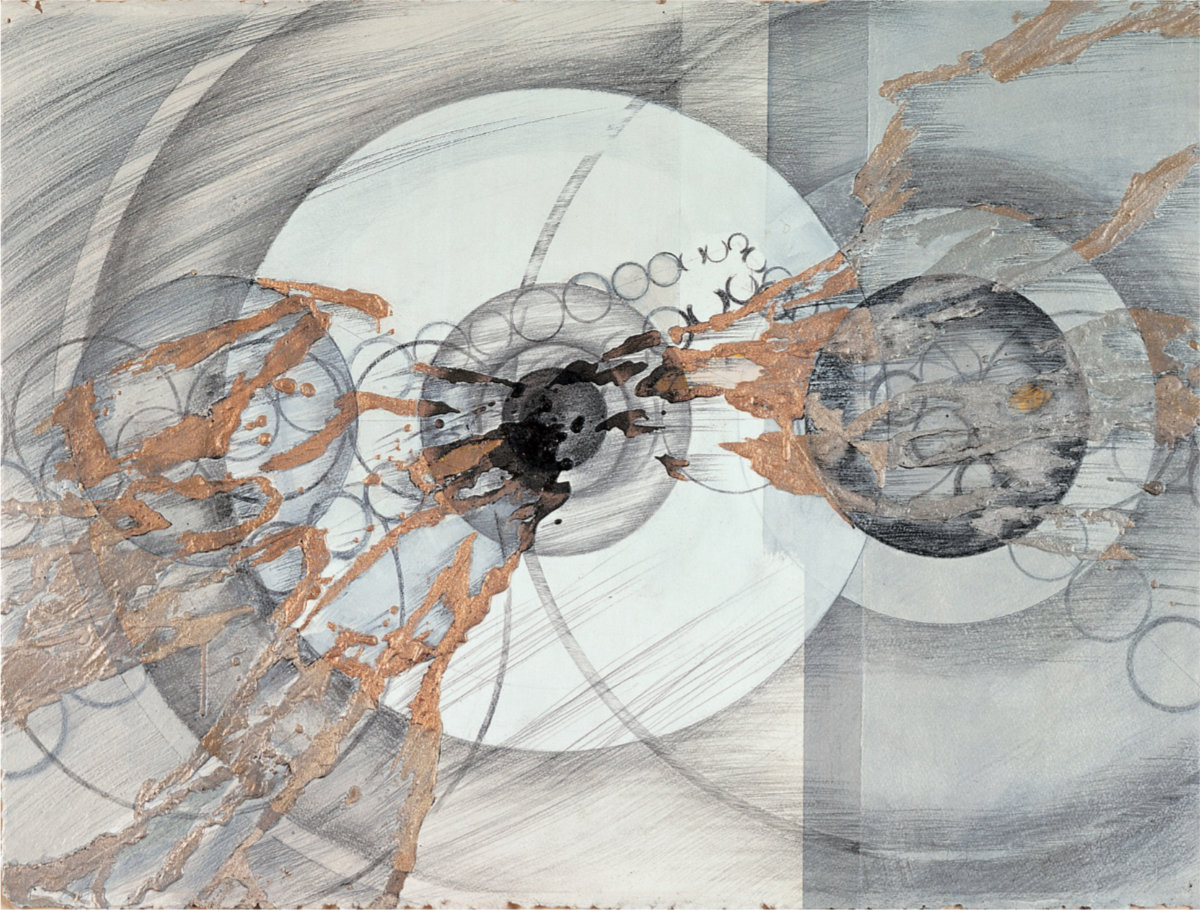

(그림 0) <Untitled>, 1981

The circle she showed in her first solo exhibition (1981) was a natural outgrowth of her femininity. Of course, I think Cho chose the circle as an existing form. But she took another step into her own style. In her painting <Untitled-81-188(1981)>, the circle visualized her own energy to challenge the pre-existing conventions by showing small dots, a big circle, and 2 semi-circles. One of the biggest paintings at her 1st solo exhibition, <Untitled-81-188(1981)>looked like the nucleus of an egg that accepts swimming sperms. This painting shows a straight forward form of biological organism. In addition, her perception of femininity is also evident in the work , which abstractly expresses the rhythm of her body cycle. These examples show that circles are not just geometric shapes, but representations of natural organic forms which are constantly moving and living. In her early paintings, circles are associated with the ideas of the womb, conception, birth, and life. Sometimes, circles are expressed as a form of light from the center, like the eyes of the Absolute looking at the world. And they also visualize certain elements that constitute the spectacles of the infinite universe with a sense of speed and fluidity. In the 1990s, her circles gradually change into formal geometric shapes based on materials. Nowadays, Cho expresses various images and objects on a circular concrete panel(called by her, Stained-Cement). Here, one can tell that the circle is extending to the material base. In other words, Cho produces concrete panels as a symbol of modern civilization, in circular or square shaped structures. On concrete panels, she sometimes draws the shapes of another circles, or attaches metal plates and objects. Through this procedure, she leaves stains of her life as ‘a kind of certain painting’. The stains in her works cross the delicate borderline between intention and chance. At this time, these stains give new life to the inorganic concrete panels and are reborn as organic structures that embrace various objects and images. Installed on the white or concrete walls of the gallery, these circular cement works show a world of variability and circulation and become a visualization of the eternity of the universe.

(그림 1) <Un and Down>, 1981

Ⅱ.

In Cho’s early works, her circles occasionally show the geometric abstraction typical of modernism. But in the 1990’s, her work reveal a mode of exploring a form with strong material properties. Cho drew circles on copper plates, thick and large Korean DAK papers, wooden panels, and canvas. For me, these works seem to be based on the exploration of the physical properties of formalist modernism. However, what I would like to point out is that we can find a slight difference from other formalist attitudes of exploring only the essence of the art as a physical property. This is because, in general, Western formal modernism artists pursue the logical essence of art based on geometric forms and solid physical properties, while Cho deals with invisible worlds such as life and the universe by using materials that have more flexibility and variability. Her approach to materials could be related to the influence of monochrome painting that was popular in Korea at the time. Although her work appears to superficially emphasize physical properties like Western minimal art, her perception of the medium has certain characteristics that imply a spiritual property. As such, her approach to materials different from others. From the beginning as an artist, Cho was not immersed in the theories and methodologies of Western modernism. By using a lot of art materials, she has used the geometrical circle not as a pure form but as a visualization of various symbols. In addition, recalling that she sought to define herself as a Surrealist artist while producing her thesis works for undergraduate, it is clear that Cho was interested in the Surrealism of transcendental rather than the conceptual kind.

The circle, which is a key element of Cho’s art, shows diverse variations as if it embodies its invisible essence. Her circles seem to have been used as suitable symbol to represent a world beyond superficial reality, showing an interest in symbolism such as divinity and the circularity of the universe, sacredness, infinity, and dynamism. In her 4th solo exhibition (1991), the circle is read as an attribute that symbolizes the secrets and principles of the universe. The works of this period were composed of matter, but they perceived the universe as a living organism. Cho sought to embody substance and reality on a picture plane that blended the geometric elements of cones and cylinders with rough material properties. The Creation, one of the works in this solo exhibition, depicts the expression of energy by drawing graffiti with metal and porcelain powder on the shapes of the eyes or circles symbolizing the abyss of the universe. From then until 2004, the main concern of her work was the circulation of universe and the creation of life.

After graduating from college, Cho began studying abroad at Pratt Institute in New York from 1979. From 1979 to 1982, she experimented with new media on the subject of circles, and in her works, (I can) tell there were complex thoughts and stimuli. When she was studying abroad in New York, the main tendencies in art were conceptual art and pop art. At that time, it can be assumed that one of the big tasks for Cho was to understand and overcome the abstruseness of conceptual art. And of all the exhibitions, she says, the Guggenheim Museum’s Joseph Beuys exhibition was one of her most difficult challenge. For Cho, many of Beuys’ artistic efforts and concepts, such as the various media he used, the irrational attributes of his work, such as the myth of shamanism, and his attitude toward self-identity and art and social practice, were major challenges. In addition, Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party shown at the Brooklyn Museum in the fall of 1980 was also a new stimulus for Cho. Seeing The Dinner Party seems to have given Cho a sense of confidence in femininity that had been perceived as passive in her earlier work. In such ways,, in New York the deconstruction of formalist modernism began. Having experienced these tendencies, Cho felt that it was time for the expansion of the visual arts field and a fundamental awakening to contemporary art. Her books, “Is This an Art?” (2004, Hyunam-Sa) and “Art with a Reason” (2016, Nosvos), reflect her perspective on contemporary art.

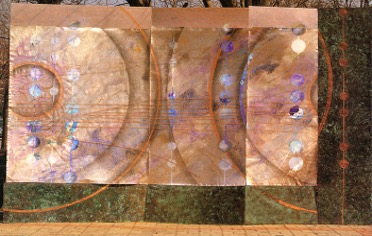

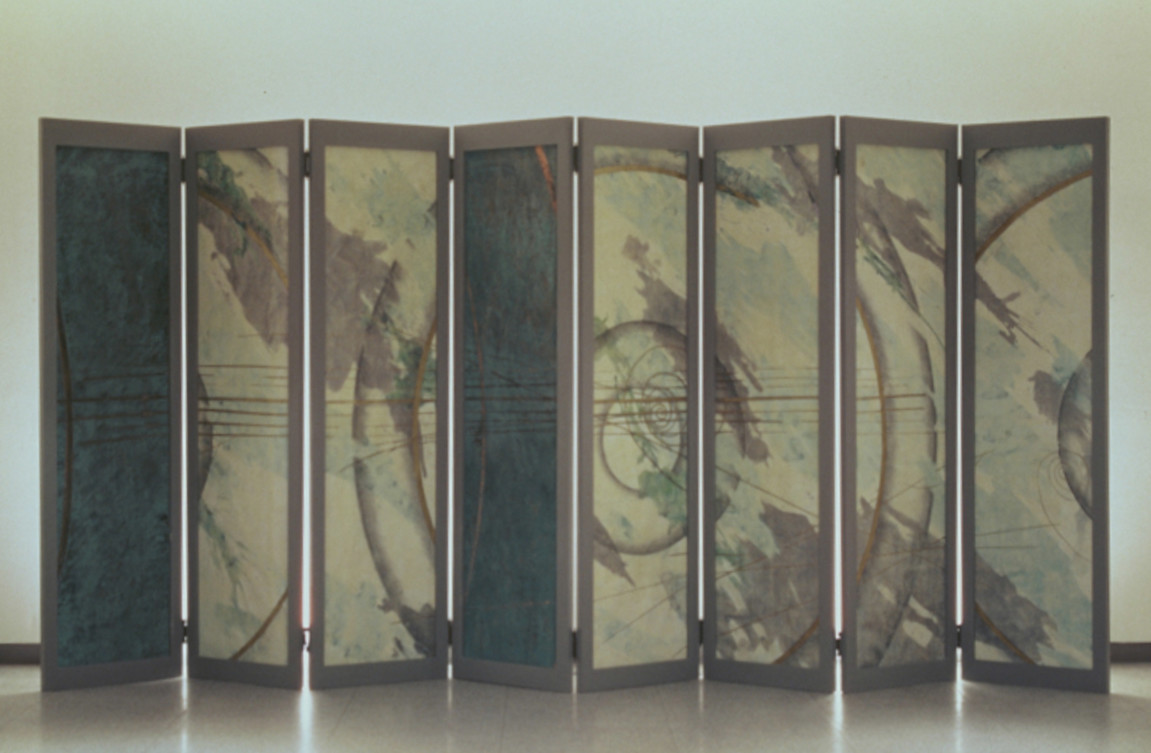

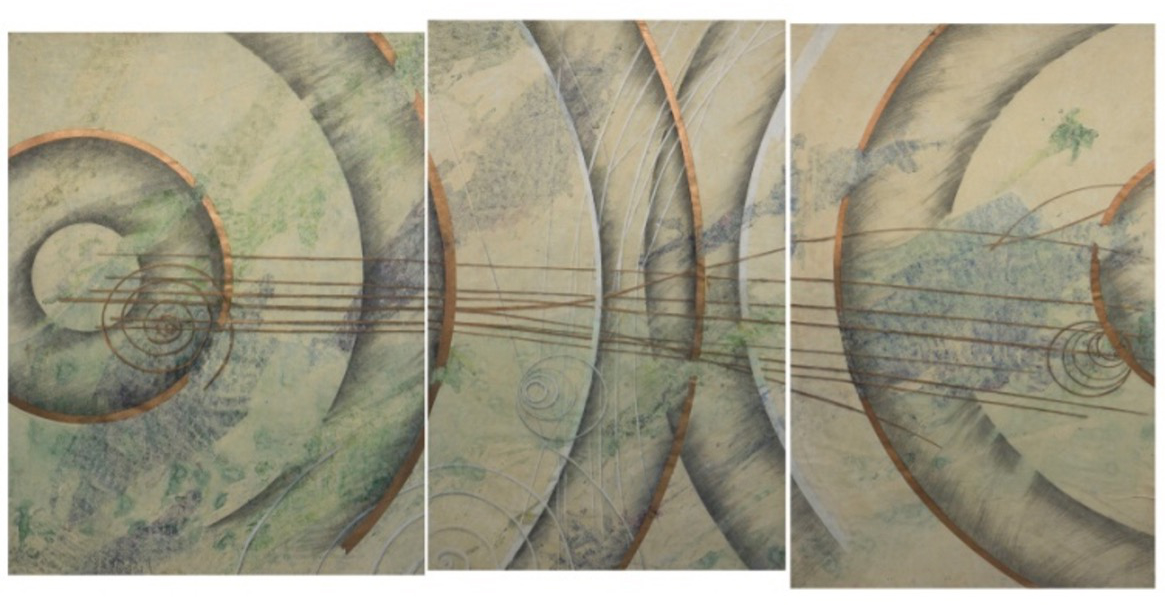

In the 1990s, CHO began to experiment with more media than before. She produced not only conventional paintings and three-dimensional works, but also computer graphics for two-dimensional works, video works, animations and a short film. Her paintings in the early 1990s sought to break away from stereotypical formalist modernism. In order to escape the cliché of flatness, she attempted to create large-scale works in which corroded copper plates are connected to thick canvas with each panel connected like a folding screen. On each connected panel, different concentric circles with a more geometric consistency are revealed, and the overlapping circles vary with motion. The circles that make up the screen are freely arranged so that they artificially distort the modernist forms that previously informed the concentric circles. Through this process, the screen vibrates, expanding its meaning and radiating energy. The painterly plane shows a more wild dynamic as it is combined with the shape of a circle superimposed on canvas or on copper plates or on Korean Dak papers with various graffiti. During this period, Cho began exploring alchemical themes as another elements of her works. In her solo exhibition Substance and Spirituality – The Alchemical Search for Painting (1991), she pondered the limitations of materiality. At that time, she had come across alchemy, which is “a spiritual adventure in relation to matter through rituals, and changes the mode of existence of matter.” At a time Cho was researching new works, molding copper plates, and experimenting with all kinds of chemical combinations, so she became more interested in the alchemical dimension to materials. Through these experiments, Cho was able to experience a strange mystery that she could not feel in her previous works. We don’t know exactly why she has been fond of using copper powder or copper plates since the early 90s. But in alchemy, copper has various symbolic meanings, such as transformation, femininity, simplicity, and spiritual enlightenment. Alchemists used copper to express psychological and philosophical inquiry and the process of material transformation. Recalling this, we can see why Cho liked to use copper in some alchemical sense.

Alchemy is the idea of “the eternity and perfection that man has sought but never found” that has occupied a great place in the human mind for centuries. In addition, alchemy has greatly informed mystical thought and philosophy as well as modern chemistry through countless hypotheses and experiments, as well as through trial and error. Thus, in postmodernism, alchemy has been recalled as an effective methodology for moving beyond the rationalist and natural-scientific thinking of modernity. Alchemy is also linked to philosophical ideas that explore the similarities between material change and spiritual growth, and these ideas have influenced modern psychology. The reinterpretation of alchemy had a great influence on Symbolism and Surrealism, and since the end of the 1960s, studies have been carried out in the context of postmodernism which seeks to interpret works of art as alchemical ideas that attempt to interpret works of art as alchemical thoughts. However, most of the theories of alchemy are limited by ideological and esoteric assumptions. Nevertheless, alchemical thought was started to be visualized from the 1990s in Cho’s work. She attempted to reconcile her own vision of alchemy with the themes of femininity seen in her early works. She describes her position as “woman’s alchemy.” Through feminine sensibilities, this “woman’s alchemy” is understood to refer to her alchemical thinking and art making attitude in order to transform substances that Cho has used. It would be most accurate to say that her alchemy is an attitude of receiving and expressing matter rather than a transformation of matter. Cho combines her rough concrete panels with soft objects and materials, which becomes her signature painting technique. In this sense, her feminism was based on sexual or gender discourse. But her art is different from general Korean feminist art which is political and social. Still I think art of Cho can be evaluated as having its own meaning in Korean feminist art since the 1990s.

Her works that maintain an alchemical feminist attitude include a series of titled Continued but Discontinuedafter 1993, The Creation(1991), Hidden but Unhidden(1991)series, and Symbolic Universe(1997). In these art works, the artist’s strong performativity and properties of matter appear together. The various reiterations of the circles that appear on the picture plane represent the universe or the energy that spreads in space, and at the same time, the will to shape the physical order through art. Her alchemy is a blend and embrace of different elements, valuing their correlations and networks rather than independence. This is because Cho believes that the universe and life exist in the interrelation of disparate things.

In 1997, Cho created and presented four-dimensional images using computer graphics to access the symbolic universe. In this exhibition, Journey through the 4th Dimension, she presents the universe as a fluid entity with images that are three-dimensional and temporality involved. By showing such images, she reveals spirituality and matter not as all or nothing, a dichotomous perception, but as an expression of a willingness to unite them through art.

In her solo exhibition Back to Nature (1999), Cho released her first video work titled Transcendental Vein as a single-channel video of the image she had been pursuing. This video gives a strong dynamism to the various painting images she had pursued, and captures a comprehensive view of the nature, universe and life, visible and invisible, materiality and spirituality. In , the three primary colors of light begin sequentially and then change to a black screen created by subtractive mixing. Afterwards, images from the early works, such as circles, a dot, and a line, are shown. The next scene shows the movement of sperm. An egg with the rapid movements of sperm is seen, and this egg appears as the image of the universe.

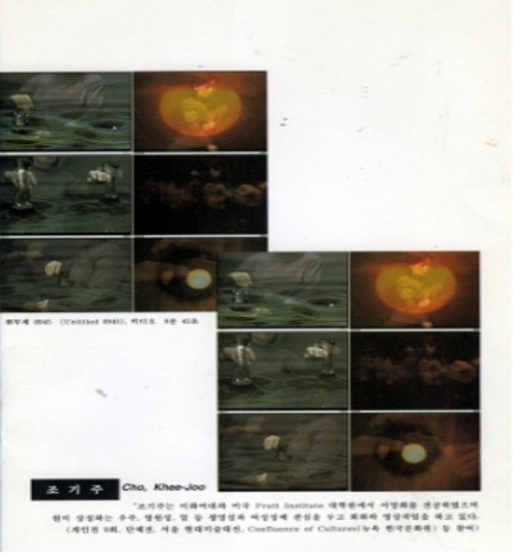

In her single-channel video work, Hand + Water + Fire (2001), Cho expands her experimentation by incorporating alchemy and feminist contexts with Eastern yin-yang thought. In other words, by juxtaposing the hand gestures of Tai Chi and the images of fire and water, she sought to convey the principles of “life” and “harmony.” This video work Hand + Water + Fire contains the principle of Eastern philosophy in which the yin and yang of water and fire are in harmony and balance with each other at the poles. And it shows that this principle of Eastern philosophy is not different from the androgynous mixture that alchemy based on Aristotle’s Four Elements (air, earth, fire, and water) was aiming for. This video Hand + Water + Fire is an attempt to give meaning to the “tenderness” symbolized by the movement of tai chi and the “femininity” that is the source of the “inclusive power” that encompasses the vast universe from the abyss. In this regard, Hand + Water + Fire is a highly symbolic work that encapsulates Cho’s work in the first half of the year. Through these 2 videos, she seems to have gained the confidence to reveal her femininity in a powerful manner.

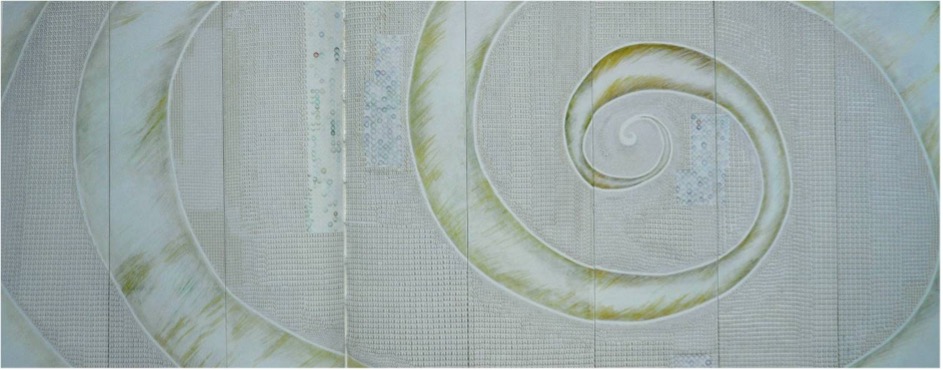

With this confidence in femininity, she was able to hold her solo exhibition in 2004, Hwa(화); Change(化), Harmony(和), Fire(火), Flower(花). Cho used materials such as pearls, beads, and sequins as the main materials for her works, creating spiral whirlwinds or flowers on the painting panels, as if small circles (spherical or hemispherical pearls, beads, circular sequins, etc.) dance.

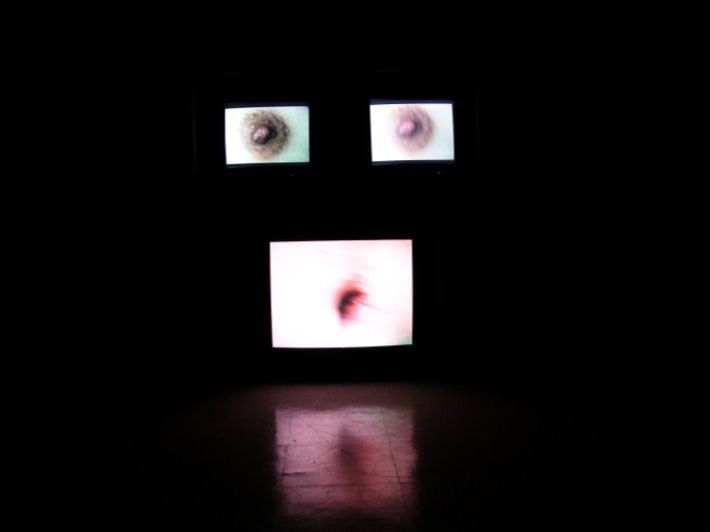

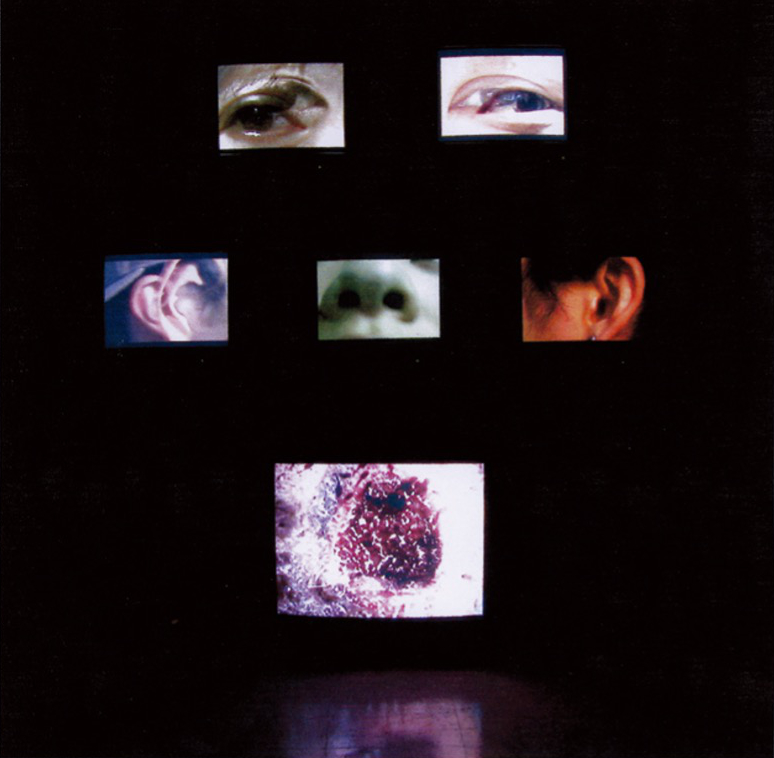

In addition, there was a series of works released in 2005 titled A (Allegory)-B (Body)-C (Circle), which presented “a circle not only as the universe, but also as a body.” In this A-B-C, another concept of the circle is explored. Here, it is the external element that constitutes the ‘human body part’. This is different from the circle used to symbolize the universe, the circulation, the egg, the womb, and life. These are the organs of the human body that secrete fluid, such as the eyes, nose, auricle, throat, navel, and nipples. These circles, which are the pores of the body, change shape and flow against the background of huge flows of liquid, or are juxtaposed in independent video works. Her videos show a woman’s perspective that reveals the desire for disorder and deviance from the individual microcosm of human beings, rather than the harmony or order of the patriarchal macrocosm. It can be seen that Cho embodied the vocabulary of post-modernist hybridity and pluralism in her videos. Based on the Yin-Yang thought, the universe, human behavior, and artistic experiments shown in her video works from 1999-2005, she produced an independent film and, since 2007, a variety of animations. In her media art, it seems she intends to add a certain kind of conceptual experimentation.

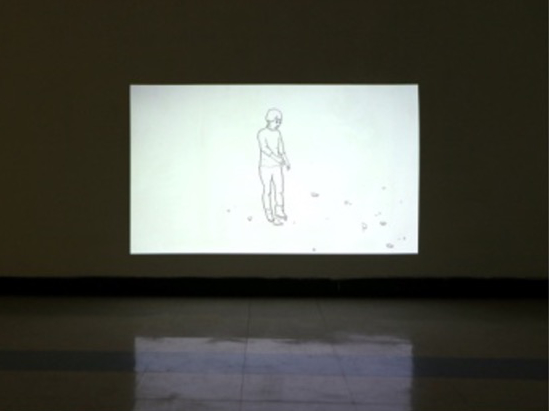

The short film Continued but Discontinued (2006) was inspired by the image of an ordinary warm woman in the Buddha Statue in Namsan, Gyeongju (Treasure No. 198). Therefore, it tells the story of a woman who opens up a new life without being subordinate to the past, while revealing a reincarnated life by intertwining the lives of a woman from the Silla Dynasty and a modern woman who dreams of becoming a ballerina. This, too, was Cho’s attempt to combine Eastern thought with feminist perspectives.

big & SMALL(2015) is also an animation with a unique theme. There are scenes of a little female protagonist hitting a big man with a bat, a woman smashing a vase, screaming, clapping, drawing circles, and tapping with needles. This work is an animation drawn with lines, so it looks calm, but its implications are quite powerful. Rather than scenes that would normally sound loud, the sound of small movements such as “drawing a circle” or “tapping with a needle” is deliberately made much louder. As in her video work Hand + Water + Fire (2001), this animation visualizes a feminist point of view with revealing Eastern thought. big & SMALL(2015) is inspired by Lao Tzu’s phrase “大方無隅大器晩成大音希聲大象無形” in chapter 41 of Lao Tzu’s “Moral Sutra”: “A loud sound is inaudible.” In other words, you can’t hear the real huge sound of nature. For Lao Tzu, the real huge sound is the sound of perfection, the sound of supreme beauty, and the Tao. Through this animation, Cho tries not only reversed sound ranking but also rearrange images. And also she intended to create visual and auditory dissonance. She visualizes the reversal of the order and norms of a patriarchal society in big and SMALL.

(그림2) <천지창조(The Creation)>, 1991

(그림3) <연속되나 연속되지 않는-93(Continued but Discontinued)>,1993

(그림4) <연속되나 연속되지 않는(Continued but Discontinued)>,1994

(그림5) <연속되나 연속되지 않는(Continued but Discontinued)> (1995)

(그림6) <연속되나 연속되지 않는(Continued but Discontinued)> (1997)

(그림7) <연속되나 연속되지 않는(Continued but Discontinued)> (1998)

(그림8-9-10) <숨겨진 것과 드러난 것> 연작, 1991

(그림11) <상징적 우주>

(그림12) <초월적 맥(Transcendental Vein)>

(그림13) , 2001

(그림14) (2001) installation view, 2014

(그림15) 2004《화; 化, 和, 火, 花》 & gallery view

(그림16) < A-B-C – Body>, 2005

(그림17) < A-B-C – Face>, 2005

Ⅲ.

Cho Kheejoo has pursued alchemical plurality not only through experimentation with materials but also by using symbolic forms and images. Then, in 2008, she introduced a white screen with almost no image. These were white flat paintings that have been painted and sanded 40-50 times on circular panels. Is it a return to the fundamental question of formalist modernism, which emphasizes essence and norms again? Cho created new works on white shaped panels. They look like monochrome paintings, which is the extreme of formalist modernism. These white paintings, which are made up of round plywood of various sizes with dozens of coats, look like a blank canvas at first glance. But, if you look closely, you can find not only the stains of various actions that occurred during the painting process but also the elements that were involved during the production of the work permeate her paintings. In some cases, the dust or brush hair had dried, and stains of liquid remain naturally. These marks are sometimes accompanied by unexpected and meaningless stains. Cho has a deep affinity even for stains or small pieces of material on the plane of the picture. In 2008, these works were presented in a series of works titled The Stains of Life. CHO’s interest in materials begins with the medium as the material used for her artworks. Then, she develops her interests not only in the found objects that she adds on the basis of materials, but also in the diverse objects and materials produced by the surplus of life. It is her interest in the stains of life that alchemically blend these together to produce an entirely new result. It seems that from the “dried liquid” stain left on the screen, she discovered an aspect of her femininity and made it one of the central aspects of her work. The stain is an indistinct remnant of existence, which gives rise to a surreal imagination that cannot be rationally analyzed. Therefore, if we try to interpret or analyze a phenomenon through stains, a problem may arise between the subject and the object, and uncertainty may occur. Because stains are like gaps between different visual perspectives. The concept of the stain allows us to look at phenomena from different perspectives and understand their complexity. In her artist statement, Cho says that it is her desire to capture visual cues about uncertainty, complexity, and otherness through stains and processes.

In Cho’s work, crumbs and useless objects that were discarded during the art-making process are actively accepted, and elements that were sometimes considered to be on the periphery of painting are actively accepted. She embraces unintentional stains as the context of her works. In doing so, she kept a distance from the modernist attitude of the past, which sought to explain the work by establishing logical meanings. In addition, Cho expanded the horizons of thought freely, escaping the world dominated by conventional aesthetic norms and principles. This is related to the Surrealism she was interested in her early work. A stain is like a passing fragrance and has a beauty that will fade away. Also, through the stain, which is the ultimate mass of life, Cho may be confirming the existence of herself and the universe.

For Cho, 2012 was a groundbreaking year. Because 2012 is the year she encountered the concrete wall. This encounter made her continue working with cement panels. Cho said she was inspired by the strong impression of the cement walls revealed in the torn Korean Dak wallpaper and the surface that contains the stains of life. This experience later became the phase that gave birth to the stained cement series. Since then, her art works have been dominated by cement panels. Cement panels, scooped out using round or square formwork, become her canvases. On the rough surface of the cement panels, Cho sometimes intervenes to emphasize the seemingly faint images, and rather actively puts various elements, such as drawings using gold leaf, other metal pieces, and hardened acrylic colors. Since this time, Cho has referred to her works as ‘Stained Cement’. Should the rough texture of the cement left with stains and traces, and the layers of countless stains of life remain in this mass, be interpreted as an alchemical encounter with the world? Superficially, the drawings on the panels, the materials or objects placed on them appear to be disparate elements that are difficult to reconcile with the rough concrete. However, Cho works carefully to ensure that the rough surface and the more subtle expressions on top do not conflict with each other. In the beginning, cement panels were mainly made of rough and thick panels. In order to hang these on the wall, quite a large bearing capacity is required, so gradually the thickness of the panels becomes thinner. She took to finely adjusting the proportions of mortar formulation to preserve its rough and natural properties, making better surface effects on the cement panels. She drew circles and grids on these rough concrete panels, and attached shapes of circles or pieces of corroded copper plates that she has experimented with. In some cases, Cho intervened by passively revealing the certain recognizable image by making a slight addition to the stains perceived by the faint recognizable image on the cement panel. The images and objects that are added to the cement panels are not meant to be anything specific, but rather are made up of meaningless or accidental, peripheral, and insignificant things. Cho is giving a rebirth to meaningless and trivial things, things that have been used and discarded.

In addition, since 2018, Cho began responding to her encounters with the fragments of discarded buildings at the demolition site of the redeveloping downtown. This gave her an opportunity to create new works. The discovery of abandoned cement chunks containing rebar and traces of other people’s lives led to other changes. As a first step, Cho carried out a ‘ritual ceremony’ to wash with water a rough-looking, stained lump of cement full of moss marks from the site. She became interested in stains because of the presence she read from the traces of other people’s lives left on the walls, and at the same time because of her interest in the many layers of life that the stains contain. By chance, Cho discovered fragments – ‘Found-Concretes’. From these, it seems that the surreal or invisible presence which could be read in the stains is related to the capture of the alchemical context in harmony with reality. Could it be that these traces came to Cho as a momentary point of contact with the fluid and indefinable nature of existence that she had been pursuing?

A trace is a mark left after life has passed. This life is not present now, but a stain of its existence that remains from a bygone time remains present. Derrida understood traces as “undecidables” that cannot be definitively said to be “is” or “not,” or as a vaguely straddling boundary between being and not being. Derrida’s core concepts, such as ‘indeterminacy’ and ‘the reason for boundaries’, all originate in this concept of traces. If, as Derrida argues, the trace is a constant slippage between presence and absence, it cannot be said which of the traces is superior. Metaphysical terms such as being, truth, center, and origin are also not perfect presences, but merely a play of unstable traces.

Cho is interested in surplus products, which are various materials and objects that are used and discarded in daily life, and she calls them “The stains of life” and becomes preoccupied with how to sublimate them artistically. The upcycling of discarded waste into something meaningful can also be interpreted in an ecological sense. Her ‘Stained Cement’ is a four-dimensional enlargement or elevation of the traces in ‘The Stains of Life’. It contains a somewhat longer accumulation of time than ‘The Stains of Life’. ‘Stained Cement’ can be said to be a continuous contextualization of the problem of the four-dimensionality of the universe, which Cho has pursued from her early works. This is because the stains or traces composed of many layers are a collection of absent presences, and those marks of surplus products extend from indeterminate space to the boundaries of time. This expansion into temporality may also be the reason why Cho continues to be interested in video work.

(그림18) <스테인드 시멘트(Stained Cement)>, 2014

(그림19) gallery view, 2015

(그림20) Short film , 2006

Ⅳ.

As we have seen above, Cho Kheejoo’s work was a journey to break away from formalist modernism, which is consistently the archetype of Western art, and to find her own unique language. The concept of the circle as a form that runs through her work was one of the formative elements that encompassed modernism and the following art movement. In her early stages, Cho chose the circle as a form for exploring the material essence and formal sources that symbolize life and the universe, and in her later period, she has used the circle as a feminist language that embodies the dynamism, inclusiveness, and plurality of the universe. In fact, beyond these distinctions, we can see that there is an energy in her heart that is full of curiosity and freedom that basically refuses to stay in the norm. Cho demonstrates this through her experiments with various media such as drawings and paintings, installations, videos, animations, and a short film, as well as her exploration of various theorerical discourses.

There are two pillars that firmly support her works, one is alchemy and the other is feminist thought. For her, alchemy is not a pseudoscientific meaning in the medieval sense, but rather an integrated and complex thought in the post-modern sense, and, at the same time, the pursuit of spirituality through ritualistic thinking about matter. Through feminism, Cho tries to break away from the patriarchal ideas and systems that have firmly built Western modernity. And Cho is following a gendered feminism that embraces things and the world broadly and elevates them into art, rather than a feminism in the political sense. In this context, we can understand why she refers to her work as “alchemical feminism.”

The various media and formal experiments she pursued can also be discussed in the context of alchemical feminism. This is all the more persuasive because it is a philosophy built on one’s own experience and life, not a conceptual approach. Cho seeks not only to dismantle the hierarchies of rational thought but also dichotomous values of the center and periphery in the modern West. In other words, Cho embraces the idea of valuing the periphery rather than the center in herworks, and includes an approach that emphasizes the relationship between objects. In addition, she is interested in traces and stains and perceives things and substance through the yin-yang thought of the East. In particular, her thoughts are concentrated in Stained Cement, which has been ongoing since 2014. However, it should be remembered that her thought is still open to freedom, instead of being rigid with ideology.

Cho discovers the stains of life in the rough and stark cement panels that symbolize man’s material civilization. She visualizes her own unique perspective on cement works. At first, the stains and traces left after the wallpaper has been torn off prompted her to begin her cement work. After that, it became another opportunity when she encountered with stains of life in the rubble of buildings revealed by the redevelopment of the city center. Cho made this possible not only through various formative experiments to give new life to concrete, but also with the alchemical technique of embracing the medium through the ritualistic procedures she has learned.

Cho’s way of dealing with materials has the characteristics of indeterminacy and non-immortality about traces or stains. She also dismantles hierarchies of the center and periphery, crossing the line between intention and chance. Her work penetrates the past and the future, and there is free spatial and temporal integration, such as the construction of structures from the ground to space. As a result, Cho’s inorganic circular concrete panels become organic beings that conceive new life and multiply new life in space, sublimated materials lifted to a spiritual level. The circle is the monad of the universe, which seems to be fixed but always has fluid energy. That is why Cho consistently uses on the shape of the circle. It is an egg, a womb, and a new universe that gives birth to new life. Cho Kheejoo’s universe and life is a world of woman’s alchemy.

Kim Chan Dong (Former Director, ARKO Art Museum)